Design for Recovery

The built environment is a massively influential component in the holistic success of patient care. Through research in evidence-based design (EBD), we have learned the powerful effects our environment has on our wellbeing, ability to heal, and recovery. With over 80,000 overdose deaths in 2020 and 20 million Americans battling substance abuse, the need for guided recovery has never been greater. Our understanding of environmental psychology, patient care delivery, and individual human needs has grown exponentially in recent years. We are now equipped with the data and research-proven strategies that will fully support the patient, the person, and the recovery process.

So, what do patients in recovery need?

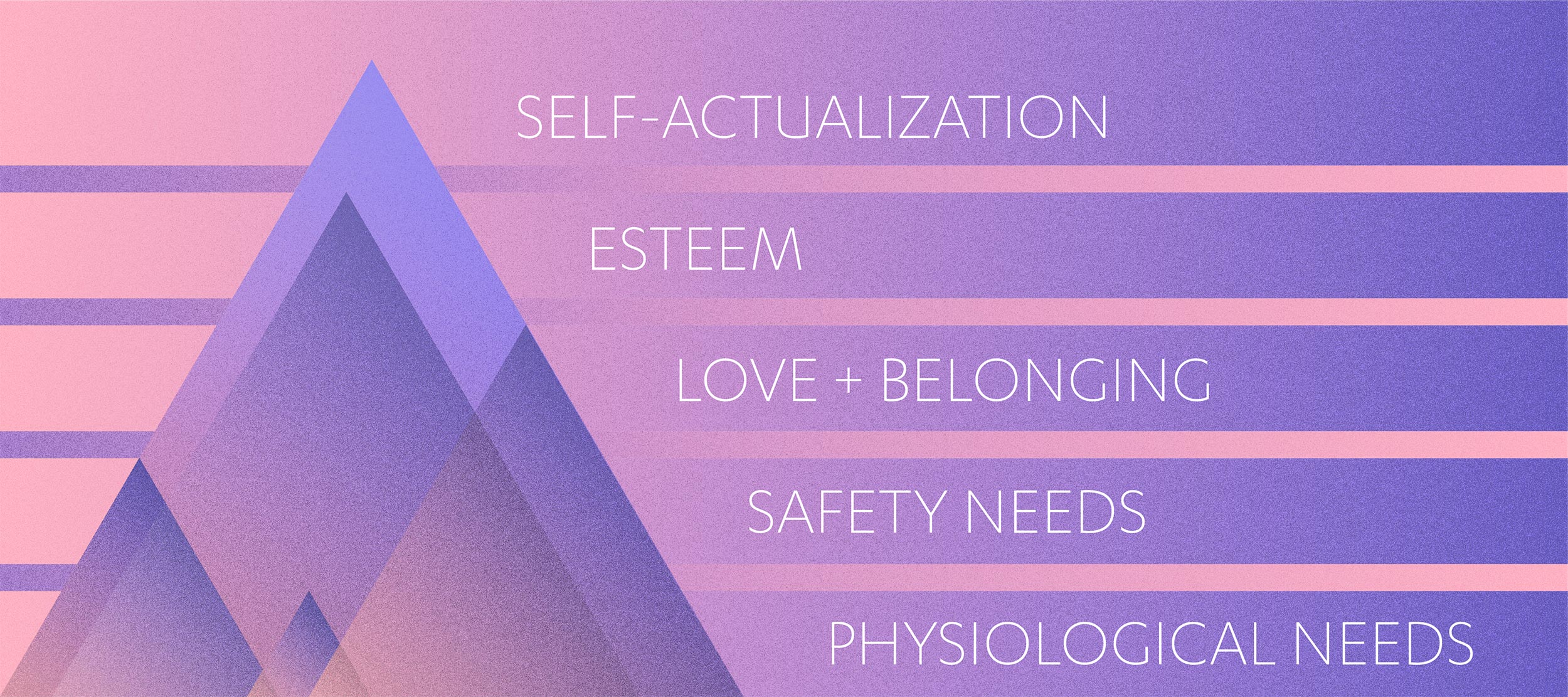

Before we can jump into design strategies, we will need to understand what it is that humans need in order to thrive. Maslow’s Pyramid has been referenced in architectural research again and again for almost 80 years for its simple, tiered ordering of basic and advanced human needs. The lowest level of the pyramid represents needs required for survival. As the pyramid rises, the needs begin to address happiness, fulfillment, and purpose. The concept illustrates the order with which these needs can be fulfilled –when the majority of the first tier is satisfied, an individual may begin to satisfy the next. The goal in guided recovery is to reach the top tier of the pyramid, yet reality is that addiction can sometimes rob an individual of the most basic needs in the lowest tier. As one can understand, the recovery process takes time, and it must help individuals rise up while in different stages of recovery and at different paces. With this in mind, we can now look to design strategies that should be applied to recovery setting to help both patients and therapists throughout their unique and personal journeys.

INDEPENDENCE

Independence leads to confidence. Confidence leads to self-respect and strength. Both lead to an increased chance at recovery. Things like feeling safe + secure and in control of one’s environment + one’s self begin to allow patients the independence they need.

Control of Space. It goes without saying that stress negatively affects recovery. One of the quickest ways to intensify stress is to eliminate environmental control. And, conversely, as a considerable number of studies have documented, when individuals have options or choices, it reduces stress and enables them to feel more in control (Winklel). A truly healing environment will offer patients as many opportunities for control and choice in as many settings as possible. The ability to alter environmental noise interruption and light glare, two of the most documented stress inducers, is critical (Ulrich). Other opportunities for spatial control might be the ability to regulate temperature and lighting in rooms, to reposition furniture, and to have control over music in private and semi-public spaces.

Control of Self. Modifying physical spaces will not bring measurable success without the patient’s ability to also control how and when spaces are used. Patients need the freedom to choose a specific environment that supports mood, phycological need, and activity – the choice between solitude versus social interaction, for example. Access should always be available to private rooms for respite, as well as to social spaces that support community and connection. Individual activity zones – mindfulness and meditation spaces – and community activity zones – fitness, art + music – should be highly accessible options throughout the day.

Closed Community. We’ve already mentioned protection from noise and light interferences. But what about activity outside of the inpatient spaces? We spoke with Dr. Deni Carise, Chief Science Officer with Recovery Centers of America (RCA), who shared that, “studies have shown that maintaining recovery from substance use disorders is difficult, and most folks see any type of reoccurrence of this disease (typically called relapse) as a failure and those who do experience recurrence typically feel shamed and judged by everyone from family to peers, to treatment systems. It’s incredibly important to make sure patients feel welcomed, safe, understood, and supported so they can have the best chance at long-term recovery.” Inpatient, or resident, spaces must allow for intimacy and trust and encourage the formation of friendships and belonging. It is critical that the design and layout of the overall plan shield residents from external stressors. Outpatient treatment, for example, could expose patients to intoxicated individuals, or Admission and Detox could expose patients to the sadness, stress, and pain of those that are just arriving. The patient knowledge that they are protected from these stressful situations is as much about safety and security as it is the comfort of knowing their environment is secure.

Simple Navigation. On some level, we all crave order and predictability in our lives. For those in recovery, this need is greater. Being in an unfamiliar place, with new people, trying to learn a new way of life is, simply, scary. Some recovery facilities are large, multi-floor units with long, meandering halls which can be overwhelming when trying to adjust to everything else. An effort should be made to make navigation as simple as possible. Clear room and directional signage, color coded space types, and a predictability to the order of spaces will alleviate confusion and (back to the top!) allow patients a greater sense of control.

COMFORT

Someone once said, there’s no place like home. Once a patient feels safe and secure in their environment, they can begin to be present and relax into the healing process. To facilitate a positive and relaxed journey, the environment should have the comforts and conveniences of home in a supportive and restorative setting.

Familiarity. Designing in elements that are reminiscent of home reduces the social anxiety that arises from experiencing new spaces. As Mary Raleigh, Vice President of Strategic Partnerships, with RCA shared, “If you put patients in a facility that they don’t feel comfortable in, they will lower their expectations of treatment and of their own recovery. If you upgrade their environment with basic comforts, that anyone would appreciate, they will feel valued, respected, and cared for and have a greater faith in the recovery and treatment process.” Furniture should be comfortable, not institutional, and arranged similarly to a home setting which might be conversational, arranged around a fireplace, or a space for one – like a lounge chair in a library. Rooms and zones can be modeled after residential settings as well. Group lounges could look similar to an open plan with a kitchen, dining area, and family room. And, just like home, resident rooms should be peaceful spaces, maximize privacy, and have secure spaces for personal storage available. In rooms with two beds, privacy options like screens or curtains could be available. Which leads us right into …

Privacy. The need for respite, as described above, is especially critical in the early days of recovery. Yet, privacy extends well beyond the concept of ‘me time’. Being in a constant state of vulnerability is exhausting and needs to be counterbalanced with the ability to escape. Planning spaces that gradually flow from public (visitor reception + waiting areas and cafeterias) to semi-public (groups rooms and lounges) to private, allow each patient the ability to fully immerse themselves in the space of their choice. One could imagine the issue with having a cafeteria too close to patient rooms, or a 1-on-1 therapy room, without the appropriate sound barriers, too close to a group lounge. Managing privacy, both acoustically and visually, will enhance the patient’s perception of comfort, safety, and security.

Biophilia. Ah, the inherent stress reducing abilities of nature. One recent study found that when residents in inpatient recovery simply watch virtual videos of nature, they experience increased positive thinking, reduced stress, and an overall improvement in mood. Considering there is no physical connection to real nature in this study, the findings are quite striking. Artwork with natural photography would have a similar effect. Bringing nature into the interior design through material selections, live plants, and access to daylight create a calming, stress reducing environment that allows residents the ability to relax. Artificial lighting that follows circadian rhythms – warm in the mornings to allow for a peaceful start to the day to cool blue mid-day for focus and energy to warm again in the evening to allow for winding down – ensures patients have energy when they need it and can get the rest they need to recover. The benefits of biophilia are so immediate that even a brief view of a garden or water element can reduce stress and anxiety (Ulrich).

EXPERIENCE

Inspiration comes from many places. The resident experience should be vibrant, diverse, and engaging. To reach self-actualization, an individual needs to be motivated to pursue personal growth and achievement. When focused on recovery and rebuilding, such a pursuit is exceptionally challenging, yet there are a number of design strategies that can support and promote this level of fulfillment.

Create an Escape. While being home is safe and cozy, experiencing something that feels like a luxury vacation can make the stay feel like a haven. A place so far from the norm, it’s easy to put real life experiences aside and become fully immersed. The location has the ability to create that retreat vibe – somewhere in the woods, mountains, or a desert oasis, for example. Yet, the concept can be built in the design itself, without the support of a magical setting, by designing to a theme in the same way a hotel would. Common spaces could be more similar to hospitality amenities. Unique attributes like a swimming pool, outdoor recreation, or even something as simple as attention to detail and design in the dining room, can be accentuated. While rows and rows of long tables feel institutional and efficient, fully upholstered dining chairs and round tables, mixed with booths and lounge seating could feel like a restaurant.

Up the Activities. The more choice in voluntary activities the better! Research has specifically demonstrated that exercise, mindfulness, and engaging regularly with hobbies improves recovery outcomes. Exercise has been shown to reduce cravings in those with alcohol abuse disorder and in this vocational fitness and nutrition training program, participants reported a greater sense and understanding of personal wellbeing, increased self-efficacy, and better physical health – reduced pain and increased energy levels. Another proven activity type is the support of hobbies. This study found that regular participants in horticulture, art, and music – the only hobby activities studied – had shorter treatment stays and were far more likely to complete treatment than those uninvolved in hobby activities. Mindfulness activities are also highly beneficial and have been shown to reduce impulsive behaviors promoting long-term recovery.

Hit all the senses. To fully immerse into an environment, we must experience it with as many senses as possible. Constant sensory engagement allows individuals to be present, attentive, and less focused on the places they have come from which can hinder or lengthen the recovery process. Let’s run through them: sight can be addressed with natural views or artwork. When a person observes and appreciates different visual scenes, such as a piece of art, complex cognitive and emotional processes, called aesthetic experiences, can arise and often lead to positive, satisfying and rewarding experiences for the viewer. Sound could be achieved through music in private or public spaces, or it could be the sounds of nature – a water element, for example. This sense can also be approached with sound mitigation techniques that reduce audible interruptions and the transmission of sounds from one space to another. Smell could be addressed with aromatherapy or the preparation of healthy foods, which also addresses the sense of taste. Lastly, touch can be addressed by including textural or tactile materials in areas that residents interact with. The most important form of touch, however, is through human connection. A simple hand on hand gesture can calm, show empathy, and build trust.

A BRIGHT FUTURE

As architects and designers, we have a responsibility to provide enriching, supportive, and healing environments to those struggling with addiction. Our mission is to improve treatment outcomes by designing a better experience for therapists, residents, and their families.

“Though no one can go back and make a brand new start, anyone can start from now and make a brand new ending.” – Carl Bard

You may also enjoy:

Retail Drop Triggers Healthcare Rise

References

Winklel and Holahan 1986; Steptoe and Appels 1989

Ulrich et al 2004; Joseph 2007